There are plenty of benefits as well as challenges associated with being in a leadership role within a company. Some people are well suited to be an entrepreneur, while others may thrive as a top executive at a large corporate entity. Not knowing which path suits you may result in wasted time, missed opportunities, and poor job satisfaction.

Having spent time in both circles, I’ve been thinking about the right path to success as measured in terms of wealth and job satisfaction. The answer, of course, depends on the make-up of the candidate and her or his skills.

A Fortune 500 executive (FFE) miscast in an entrepreneurial role is unlikely to seize the opportunity to join the happy land of Unicorns with the wealth of the “one percent”. They may be able to build a worthwhile and sturdy business, but capture only a fraction of the value that a peer in a large company will achieve with much less personal sacrifice. Thank the miracle of stock options coupled with buybacks for that.

It’s not that corporate executives in large companies don’t work hard. But the resources and established infrastructure available to them can make tasks easier. The flip side is that startups with nimble and entrepreneurial leaders can often turn on a dime. Of course, all of this is completely situational. Every case is different.

One thing is clear, however, to succeed as an entrepreneur requires skills which often undermine success in a large, successful company – and vice versa.

Entrepreneurial Skills

Rat-like Cunning: This trait is necessary for entrepreneurs looking to identify and invade the turf of the established target market and steal their valuable cheese. Conversely, a FFE must radiate trust to succeed and therefore suppress these instincts. The small group of executives running Fortune 500 companies (and getting rich doing so) live in a fishbowl and know each other only too well. Rodents are quickly identified and removed, if not exterminated.

Redoubtable Ego: For entrepreneurs, it doesn’t hurt to have an ego that verges on narcissism. Entrepreneurs are a volatile mix of bravado and insecurity that propels them through the almost daily moments of euphoric triumph and crushing defeat. The victories are viewed as the singular result of the entrepreneur’s gifts and obsessive commitment. The failures are always misattributed to the treachery and/or incompetence of others.

996 Focus: Wringing the long and demanding hours of a Chinese factory employee (9am to 9pm, six days a week) out of the beleaguered startup team means leading by example. Entrepreneurs are always working. That includes being visible and active in the office, as well as responding to emails at 2 am. This level of commitment is what enables 10 employees to outperform 1,000 – at least at first. But that pace isn’t sustainable and runs aground in the Fortune 500 world of work/life balance.

The Guts of a Burglar: Some entrepreneurs essentially steal money from investors and employees by convincing them that a generally vague and gauzy vision of the future will pay off in huge multiples. They do so by ignoring, dismissing or hiding inconvenient facts. They do whatever is necessary to sell the vision – including bending the truth. Many entrepreneurs seek to emulate Steve Jobs’ ability to create a “reality distortion field,” which was perhaps his most important attribute.

Putting the Cake Under the Icing: It’s not a rarity for entrepreneurs that a feather weight prototype is deemed industrial strength and rushed to production. It’s somehow made to work by an exhausted team in a manner that would be unsuitable for a more mature and stately enterprise. A startup will remember this as an inspiring break-through, while an established company will quiver at the thought it might ever happen again.

Be Careful What You Wish For: A talented thirty-something executive in the upper echelons of a large company may tire of doing the calculus of how to land in a corner office. They may instead yearn for the opportunity to lead a startup, believing that the encrusted layers of senior management above them are dinosaurs ignoring their own imminent extinction.

This ignores the current investor sentiment that hugely rewards cash generating businesses that predictably pay out good dividends and can also fund stock buybacks.The overriding objective for senior management at large corporations is to avoid risk and, worse, catastrophes (such as what happened with the Boeing 737 MAX) while accumulating options and restricted stock grants.

Doing a Gut Check

But if the impatient maverick still contemplates jumping into a startup venture, it is important to do a gut check on the skills noted above. If only partially equipped, mavericks may fall into the trap of creating good, useful and profitable companies that fail to develop the escape velocity that is a prerequisite for a successful exit.

Escape velocity translates into 50 to 100% year-over-year revenue growth for half a decade or more – no easy feat. As a result the entrepreneur may find themselves saddled with a company that pays a slim salary for the prime years of their career compared to the Fortune 500 executive. And after 20 years they may on;ly own a piece of a business that can be acquired for little or no money.

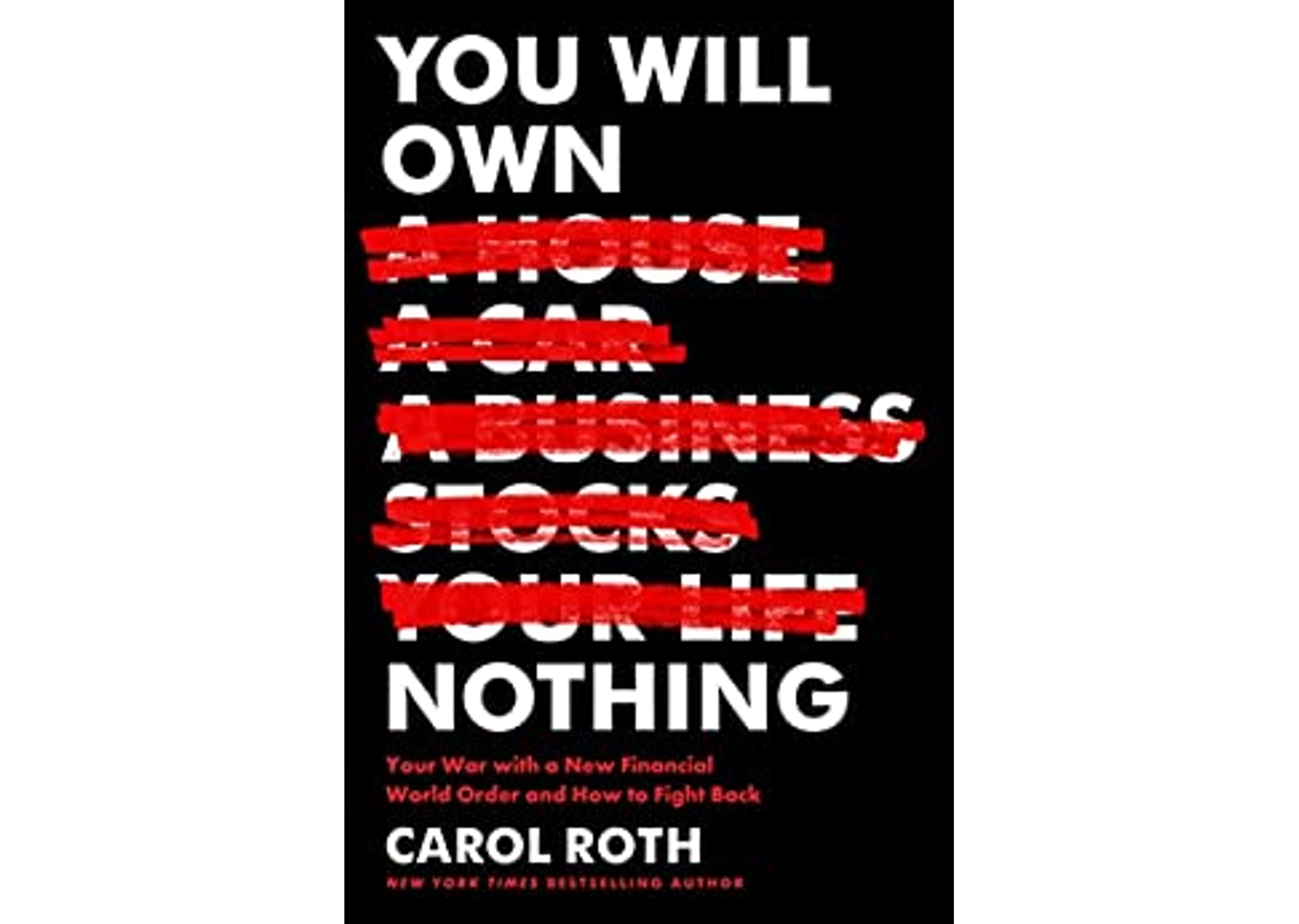

Carol Roth’s glossary, includes the phase Return on Ego (R.O.E.), calling out instances when decisions are driven by a desire to feel important or special – instead of as a matter of good business – you are driven by R.O.E. A business card with startup CEO on it sounds great, but the psychic compensation fades if it doesn’t yield the ROI of the duller but safer career in a large and even modestly successful Fortune 500 company.